Sidestepping the Limitations of Collection Catalogues with Machine Learning and Wikidata

Rhiannon Lewis and John Stack

The Heritage Connector project seeks to understand how existing digital tools and methods can be used to build relationships at scale between inconsistently, and at times thinly catalogued, digitised collection objects. Online collections have been with us for around twenty years now, and their digitisation has enabled access to databases with a wealth of collections knowledge. However, these databases have determined, and limited, how this collection knowledge was structured and accessed. Machine learning presents an opportunity to build links at scale through knowledge graphs between Wikidata and museum collections, so that we can begin to acknowledge and overcome these limitations.

Heritage objects in online collections

Since the late 1990s, increasing volumes of cultural heritage collection objects have been published in online collections. More recently, new forms of imaging (deep zoom, 3D scanning, etc.) have enabled ever greater exploration of those objects. While new forms of aesthetic exploration of objects offer ever richer user experience for individual objects and potential for new forms of research, the user still needs to discover these “enhanced surrogates” through online collection web interfaces. This can entail any of the following:

- knowing about the collection’s existence;

- understanding that it may contain relevant contents;

- knowing that content is available online;

- navigating the common pitfalls of text search: using search terms that align with the terms in the collection catalogue, having the desired content appear near the top of the results, potentially making multiple searches;

- being able to see the relevance of the content to the search;

- ideally, being able to navigate from that content to related content.

Even though enormous amounts of collection content has been digitised, there are multiple barriers to its discovery.

How those collections have been structured

Many of these discovery steps are driven by catalogue data. These records are usually stored by a collection management system in a relational database whose structure can be used to power online search and browse features. For the most part, these catalogues pre-date digitisation and their origins lie in the needs of collection management: accession records, location, loans, reports, conservation, hazards, etc. Then, a subset of these fields are used to populate the object’s online record.

The records may also have been augmented by new cataloguing data which has been specifically implemented to improve the online experience: indexing, interpretation texts, manually created links to other resources, etc. In spite of this discovery and exploration of those objects remains, however, primarily driven by the collecting institution’s catalogue.

Challenges, limitations, and their causes

Through this approach, huge volumes of cultural heritage material are available online. There are, however, some limitations to this approach that are common across the cultural heritage collection sector.

Collections

- Collections can be extremely diverse in content – for example, the Science Museum Group’s collection includes unique scientific instruments, mass-produced products, artworks, ethnographic objects, rail vehicles and more. These disparate areas would benefit from specific approaches to cataloguing and discovery.

Legacy of cataloguing methods

- Approaches to cataloguing have grown organically, often over decades, and are frequently inconsistent within a given collection.

- Cataloguing is labour intensive and generally, records are thin or partial, and many objects are potentially similarly catalogued.

Cataloguing data

- Collections and their contexts are complex and hard to model in datasets at scale and collection catalogues are inevitably reductive.

- Application of controlled vocabularies is variable and uneven, limiting browsing interfaces as computers rely heavily on controlled data for such interfaces.

- Collection subcategories are used for a variety of purposes and are frequently hard to alter, the result of which is that it is problematic to use these as useful entry points to explore collections.

- Object terms that are no longer in use or understood beyond specialist knowledge relate to objects, therefore making free text search hard to navigate without prior subject knowledge.

Difficulties traversing collections by theme/object

- The same object is likely catalogued in different ways in different institutions’ collections as the catalogue itself tends to view the object through the lens of the institution’s broad subject domain.

- Across multiple institution’s collections it is hard to get a handle on the overall contents of collections quickly and the relative strengths, volumes and contents of each in different areas.

- Collection catalogues tend to include very few or no links to external sources be they other collections or related material.

- Aside from a handful of aggregators such as ArtUK and Europeana, discovery across disparate collections requires multiple searches and manual collation of results as each collection website is effectively an island and the aggregators inevitably inherit many of the limitations of the individual collection websites.

Enter machine learning

Previous and current approaches to digital access to collections have been based on a model where data is tabular, although structured in a relational database, which does afford sophisticated searching to the extent that the underlying data supports it.

Through machine learning, there is a step change underway in the capability of computers to solve problems. Machine learning can provide better results for existing questions, it enables asking new questions and can be applied to new types of data. It can do these things at scale and at speed.

Areas of potential

From our analysis, machine learning presents opportunities for digital collection management in these areas:

- improve browsing interfaces where those are currently limited by the available collection data

- enhance search by keyword where that is currently limited and where presentation of results in an ordered list is problematic.

- extract information (datapoints) from the free-text description and interpretation fields

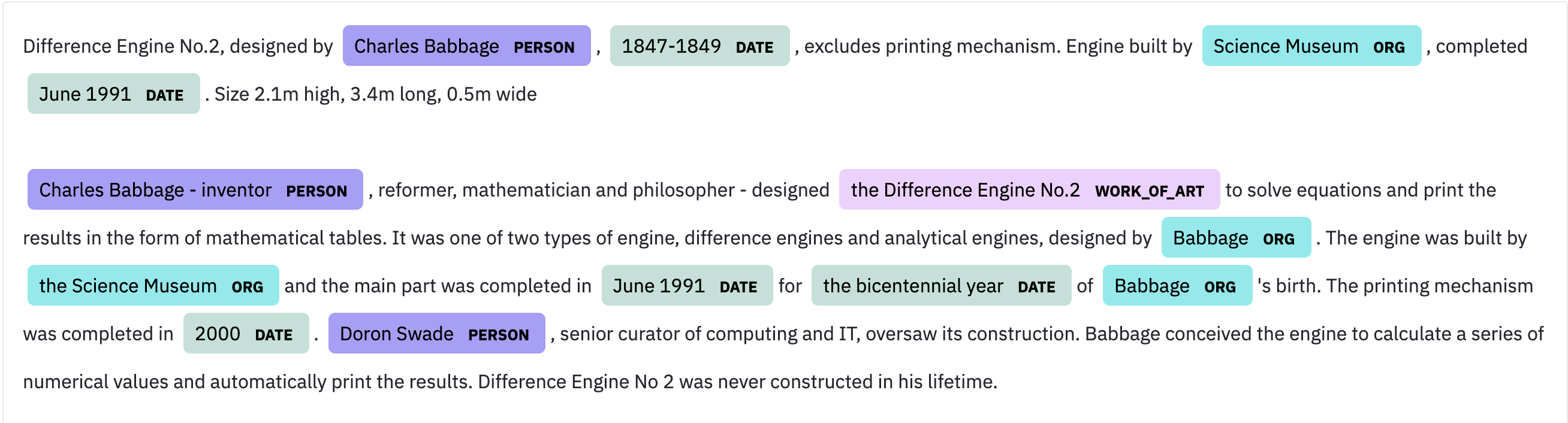

Screenshot description field of Difference Engine No.2, designed by Charles Babbage, built by Science Museum with named entity recognition testing

Screenshot description field of Difference Engine No.2, designed by Charles Babbage, built by Science Museum with named entity recognition testing

- create thematic and topic entry points that provide users with entry points to areas of the collection(s)

- enable-cross collection linking and discovery so users can rapidly explore larger and more diverse volumes of material

- offer onward links to related material in other collections and related sources

- increase usage of collections through surfacing deep content more effectively

- facilitate serendipitous discovery of material by providing a wealth of surrounding material and contextual content

- generate links into knowledge graphs and third-party datasets that surface new data and facilitate new forms of cross-disciplinary research

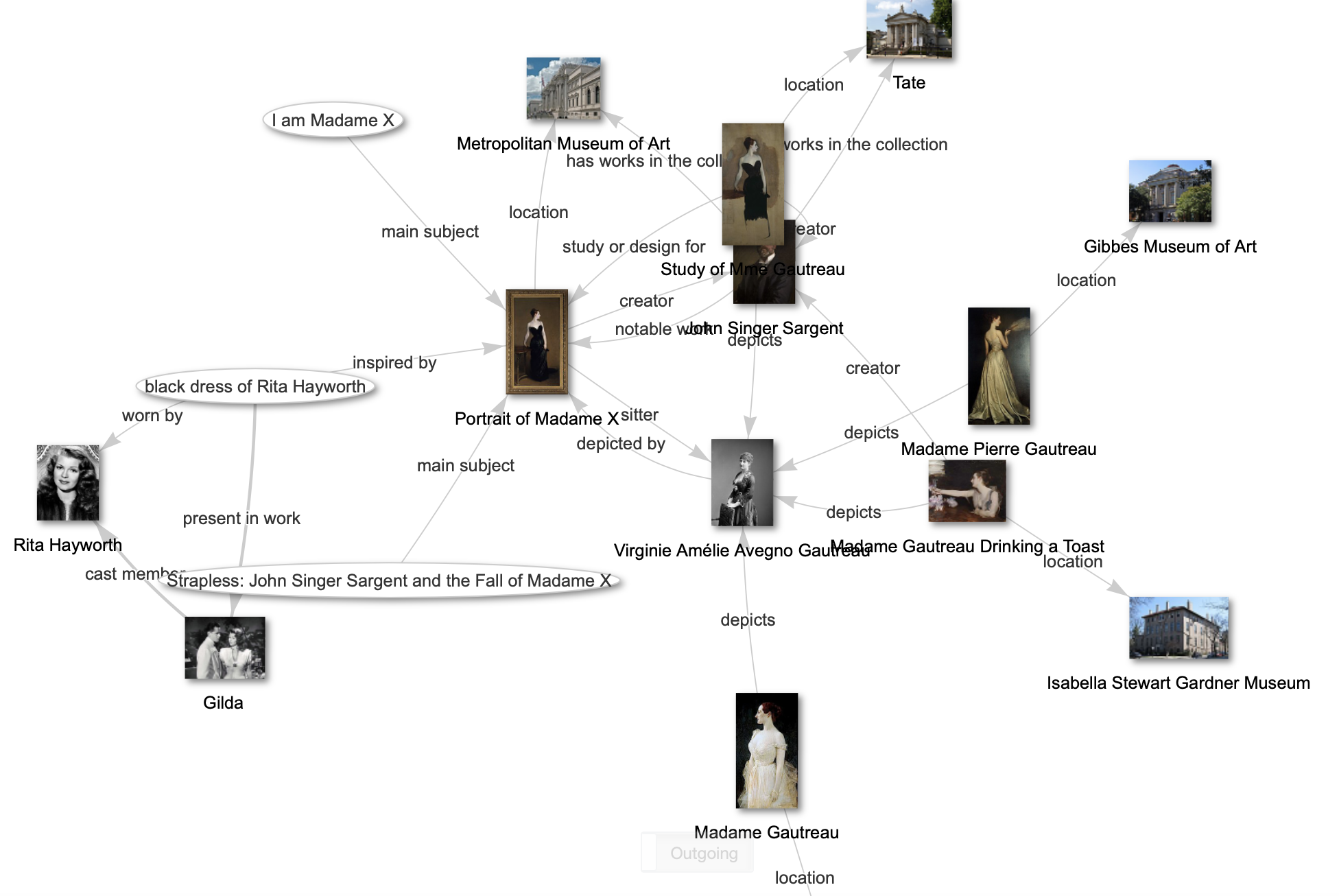

Screenshot of Wikidata linking museum collections starting with a Portrait of Madame X by John Singer Sargent from The Met’s collections’, which went on to inspire a dress worn by Rita Hayworth - Wikidata query

Screenshot of Wikidata linking museum collections starting with a Portrait of Madame X by John Singer Sargent from The Met’s collections’, which went on to inspire a dress worn by Rita Hayworth - Wikidata query

- explore playful and experimental approaches to collection access which will broaden audiences.

Heritage Connector

In Heritage Connector, we’re exploring how to realise the areas of potential outlined above using machine learning techniques on the existing collection(s) catalogues and other datasets to build a knowledge graph. This knowledge graph will be linked to Wikidata. Wikidata is the free, open, linked, multilingual and structured database which underpins Wikipedia but which is also a tool in its own right. Today, Wikidata contains over 89 million items structured as a linked data and includes references to dozens of external data points in cultural heritage collections.

Four months into the project and among the emerging areas of potential that we are seeing are:

- Clustering of related content which might be used to create new features such as improved related content

- Creating thematic entry points to “neighbourhoods” in the Science Museum Group’s collection

- Being able to generate area visualisations to show content density, relative to volumes of content and record depth

- Presenting the entire collection in forms explorable by a larger number of dimensions than exist in the (relational database) collection catalogue

- Making links to Wikidata that will enable us to ingest related Wikidata entries into our search index to improve search, discovery and browsing; enable multilingual features; and present additional fields held in Wikidata that are not within the collection catalogue

- Using Wikidata as a “Rosetta Stone” to provide links to other datasets, to ingest content from those datasets, and to provide richer interfaces

Emerging considerations

As Heritage Connector has shown areas of potential for use of machine learning methods in building a knowledge graph to connect collections to Wikidata, some areas of exploration and scrutiny over the next period of the project have emerged:

- What are the contexts in which Heritage Connector’s data might be used? Are there interfaces and applications emerging as possibilities from it?

- How can “fuzziness” and uncertainty of machine-learning-generated links/content be presented?

- How is it best to define the edges of who and what is not included in the catalogue, in other datasets and in the various software toolkits being used?

- Are already marginalised / under-represented groups in collections moved further to the margins through existing or historical data usage?

- What are the relevant ethical issues in machine learning generally, and how do these manifest when programming to learn specifically from museum collection catalogue data?

- Transparency of connections - document how links were created and consider how this transparency might speak to different audiences.

- Need to explore the possibility of users feeding back on the usefulness of the outputs and potentially incorporating this into the output interfaces e.g. flagging poor links / upvoting good links, etc.

Digging deeper into these questions will be the focus of some of our forthcoming blog posts.