A Brief History of Research into Museums’ Online Collection Audiences

John Stack

Introduction

In 2016, the Science Museum Group undertook a comprehensive piece of research into audiences for online collections and associated narrative-based content. The findings of this research are summarised in a blog post which includes the following outline of ways in which the Science Museum Group could improve the experience for users:

- We have a diverse audience — some of whom want encyclopedic results and some who want a short snapshot;

- This might be the first engagement a user may have with the Science Museum Group — knowingly or not — and we want it to be engaging;

- Users don’t currently browse our objects;

- Users do not necessarily know what is in the Science Museum Group collection;

- Users may be interested in broader themes rather than specific objects.

This research has implications for the aspirations of our [collection] discovery tools. We want these tools to:

- Encourage meaningful browsing amongst our collection — inspiring and surprising users by what we have in the collection;

- Be usable for audiences looking for both a content “snack” as well as audiences looking for deeper information;

- Explore mechanisms to showcase the breadth and diversity of the collection, but for this to still be relevant;

- Explore whether we need to tailor browse interfaces for different areas or subjects within the collection — they may have different audiences;

- Discovery tools can be a separate layer or can be integrated into the object pages themselves.

As we work on the Heritage Connector project, and consider how machine learning and other techniques might help deliver new forms of searching, browsing and discovery, we’ve reviewed other studies into the audiences for museum online collections. The following is a summary of that review.

2007

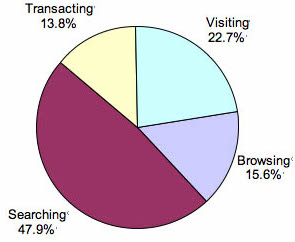

The notion of “browsing” behaviours in museum online audiences appears in the earliest studies of museum online audiences such as that by Darren Peacock and Jonny Brownbill at Museums Victoria in 2007 which identified four high-level motivations: visiting (22.7%), browsing (15.6%), searching (47.9%) and transacting (13.8%).

2008

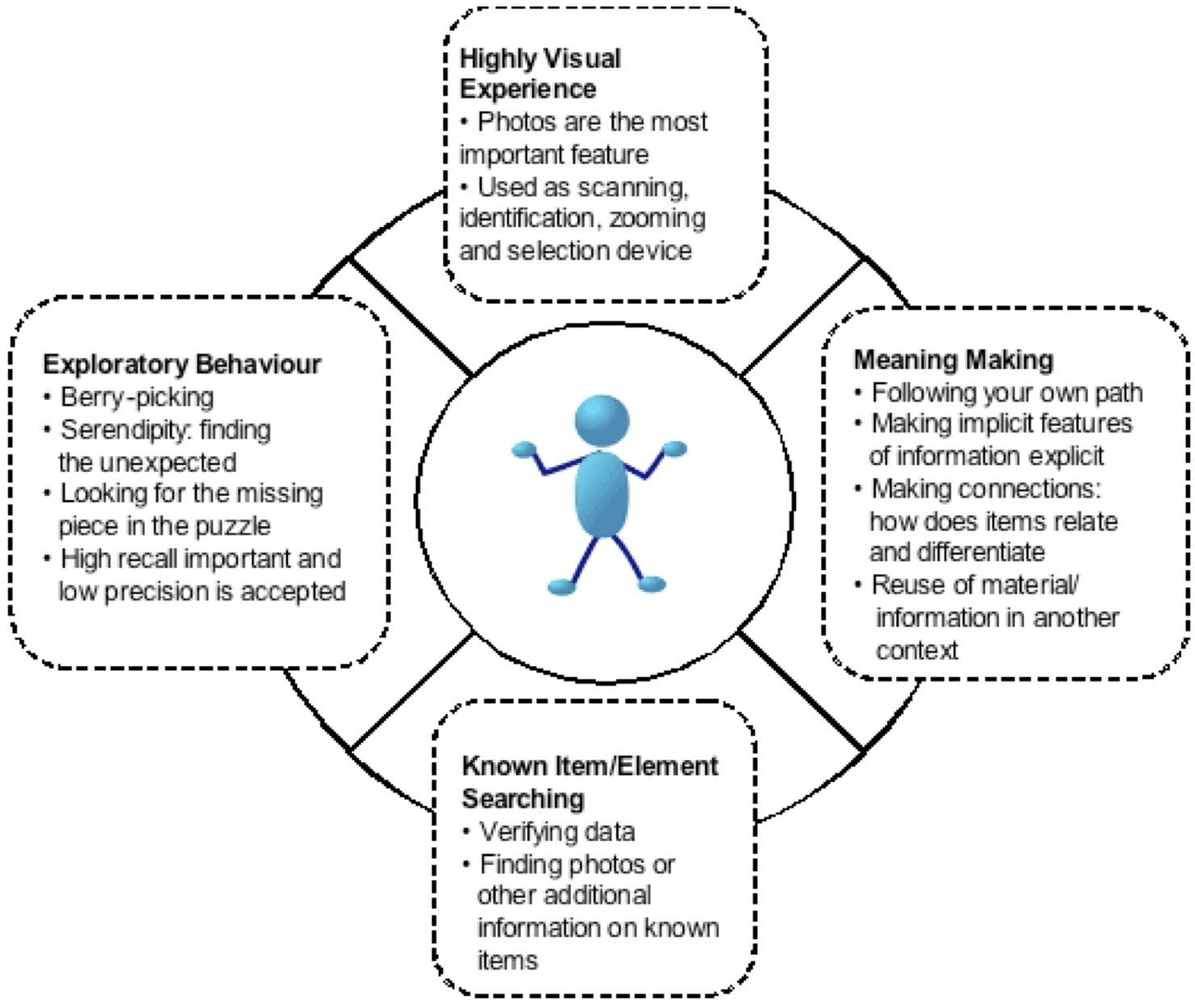

In their 2008 paper Exploring information seeking behaviour in a digital museum context, Mette Skov and Peter Ingwersen analysed online museum visitors’ information seeking behaviour and found a broad range of users from diverse backgrounds who had very varied goals and information needs. From this they identified four behaviour types: highly visual experience, meaning making, exploratory behaviour and known item/element searching.

2011

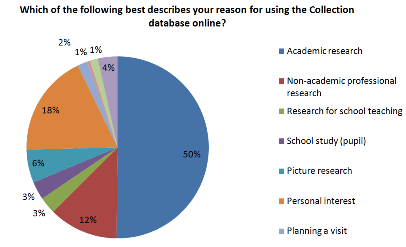

The 2011 study by Claire Ross and Melissa Terras focused in depth on the digitised collection of the British Museum and on the audience who were using the site for teaching (3%), studying (3%), academic (50%) and non-academic research (12%), personal interest (18%) and picture research (6%).

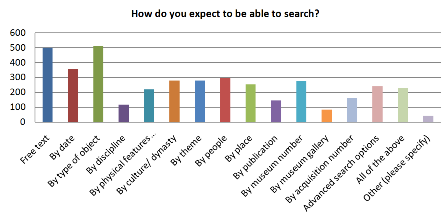

As well as motivations, the study also explored what the users were looking for and how they expected to be able to search, with search and browse as a facet of most of the identified audiences.

2012

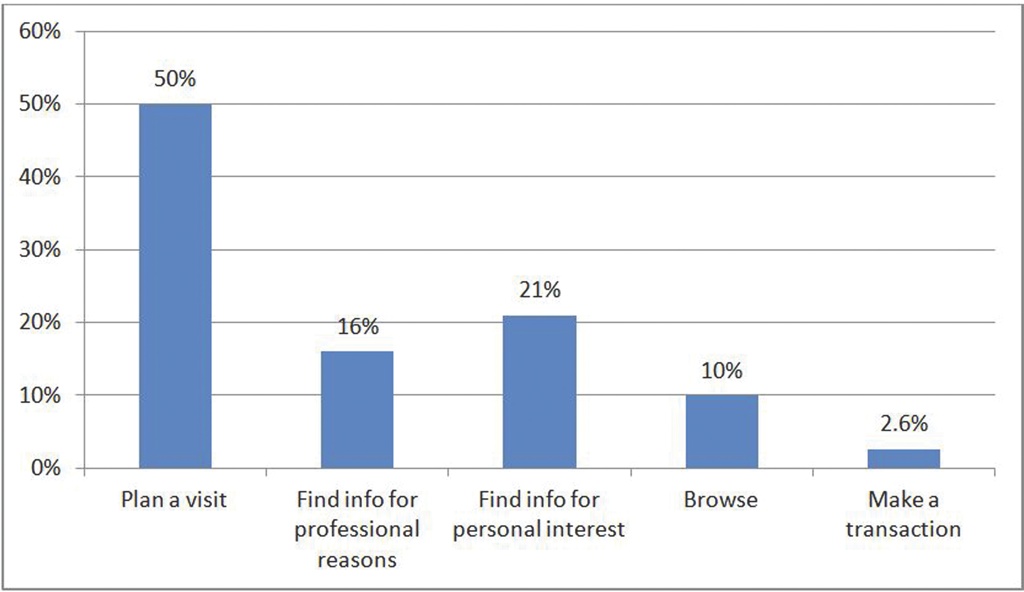

The 2012 study by Silvia Filippini Fantoni, Rob Stein and Gray Bowman undertaken at the Indianapolis Museum of Art (now Newfields) established that 10% of their online visitors as “browsing”, and breaks down “information finding” into two categories: “for professional reasons” (16%) and “for personal interest” (21%).

In each of these first three studies, the search/find and browsing categories point toward motivations that may be considered ways in which museums are fulfilling their missions digitally by bringing its collection into the online space and in each case a significant proportion of online visitors are motivated by accessing this type of content.

2014

The 2014 paper Museum Web search behavior of special interest visitors by Mette Skov and Peter Ingwersen identified four main characteristics of online museum visitors’ searching behaviour: (a) searching behaviour has a strong visual aspect, (b) topical searching is predominantly exploratory, (c) users apply broad known item searches, and (d) meaning making is central to the search process.

2015

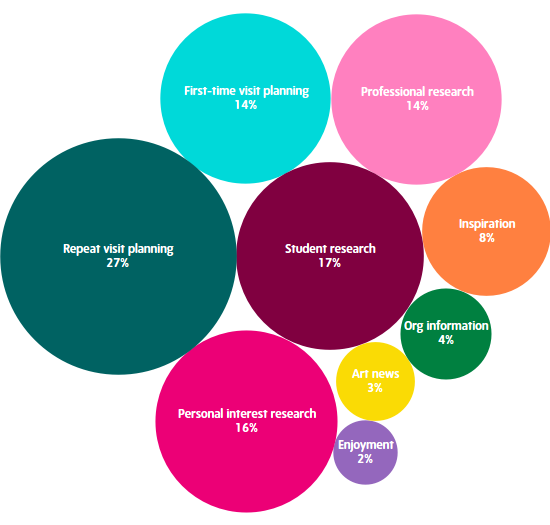

The 2015 paper by Elena Villaespesa and John Stack further explored motivational categories through work at Tate by breaking down research motivations into personal (16%), professional (14%) and student (17%) research, and unpacking browsing behaviours into inspiration seeking (8%) and enjoyment (2%).

In 2015 Europeana undertook a campaign (pdf) to promote the launch of a new collections portal and identified two target audiences:

- Culture vultures: this group includes cultural heritage professionals, involved in learning, researching or the teaching of arts and humanities, ‘expert amateurs’ in some subject of cultural heritage, or people who are interested in culture and cultural heritage more than most;

- Culture Snackers: citizens who are not actively seeking for heritage content but like to see or interact with engaging items, for example in their social media platforms.

2016

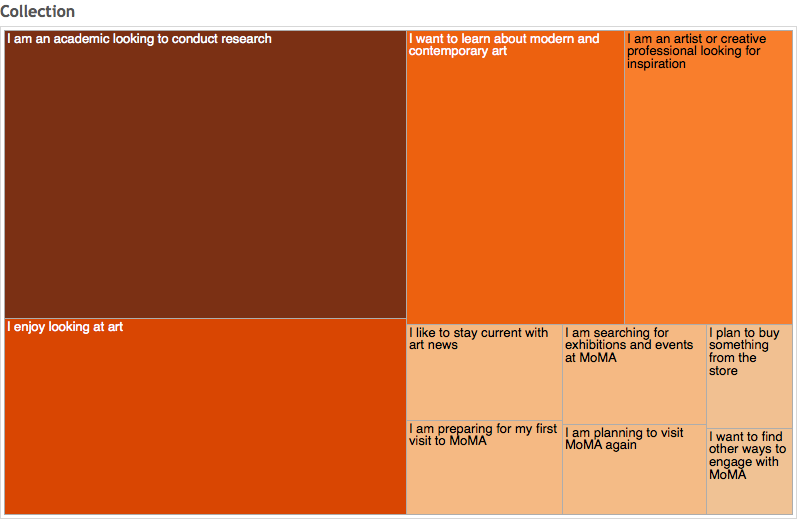

A 2016 study by Fiona Romeo at New York’s Museum of Modern Art explored the motivations of those using the online collection, highlighting academic research as the largest motivation followed by looking at art, learning and seeking inspiration.

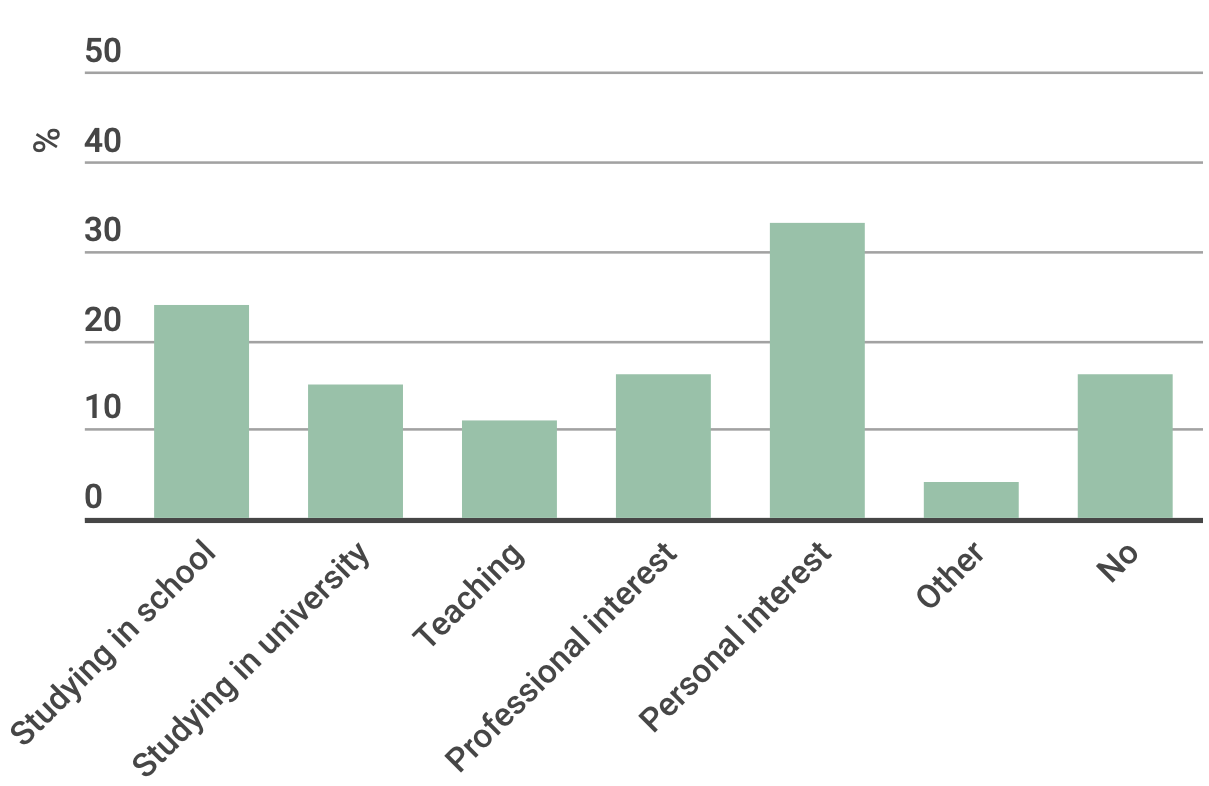

The Science Museum Group’s 2016 study – summarised in a blog post by Emily Fildes – found that the Group’s online collection that audiences are from diverse backgrounds: studying in school (24%), studying in university (15%), teaching (11%), professional interest (16%) and personal interest (33%).

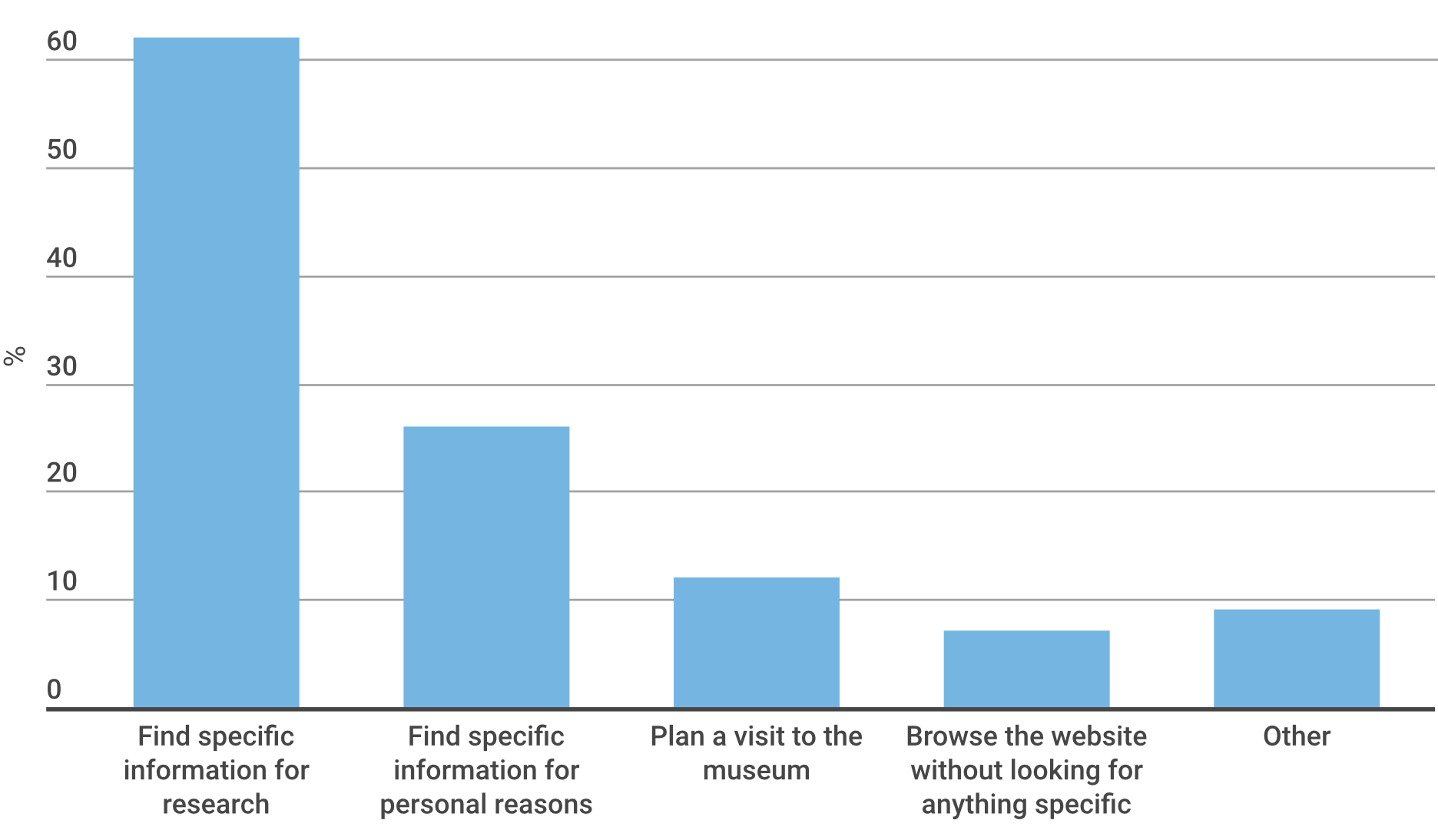

The study also found a strong motivation to find specific information for research (62%) ahead of finding specific information for personal reasons (26%) and general browsing (7%).

2017

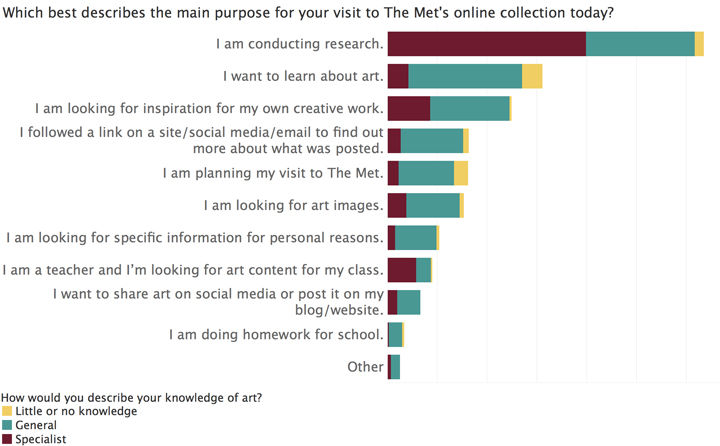

The 2017 study by Elena Villaespesa looking at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection website visitors, extends the motivation approach to include “social media sharing” and “following link from social media or email”. Villaespesa goes on to argue that, “Motivation is just one variable [and] looking at the same chart but adding our users’ knowledge of art shows us the diversity and range of users within the same motivation category.”

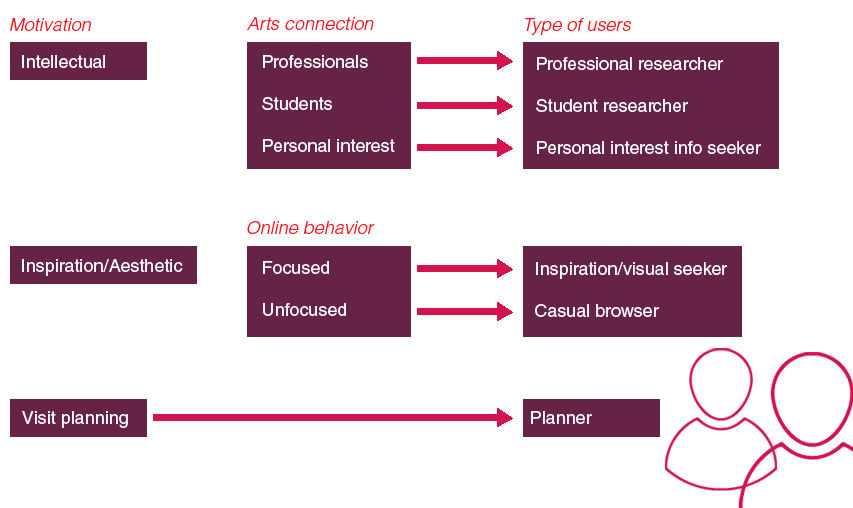

The resulting audience segmentation for the Met’s collection defines three core motivations: intellectual, inspiration/aesthetic and visit planners, with intellectual broken down into three subcategories (professional researchers, personal-interest information seekers and student researchers), and inspiration/aesthetic containing two subcategories: inspiration seekers and casual browsers.

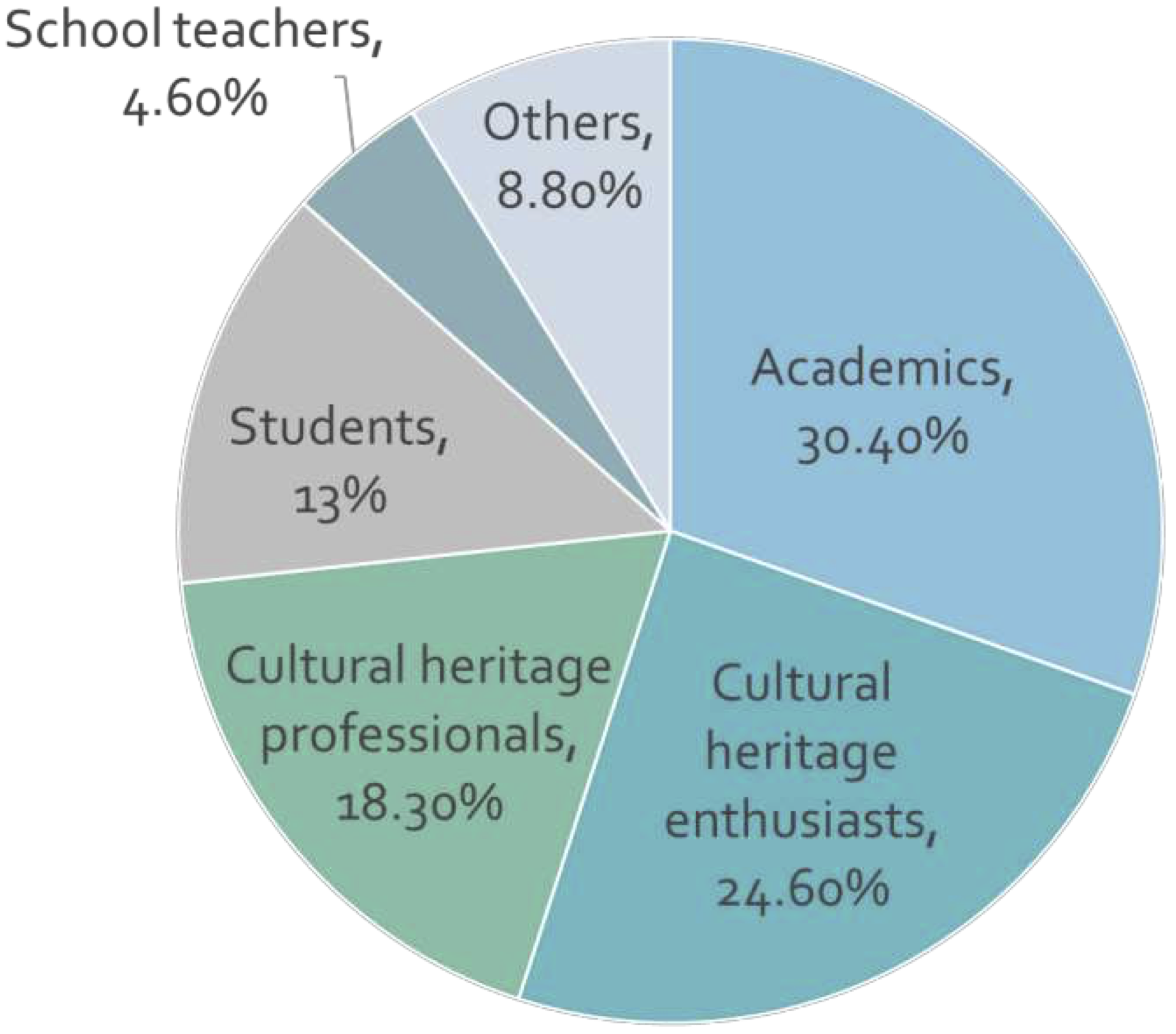

The 2017 paper Europeana: What Users Search For and Why by Paul Clough, Timothy Hill, Monica Lestari Paramita, and Paula Goodale reviewed searching behaviour on Europeana. They identified the core audiences as academics (30.4%), cultural heritage enthusiasts (24.6%), cultural heritage professionals (18.3%), students (13%), school teachers (4.6%) and others (8.8%).

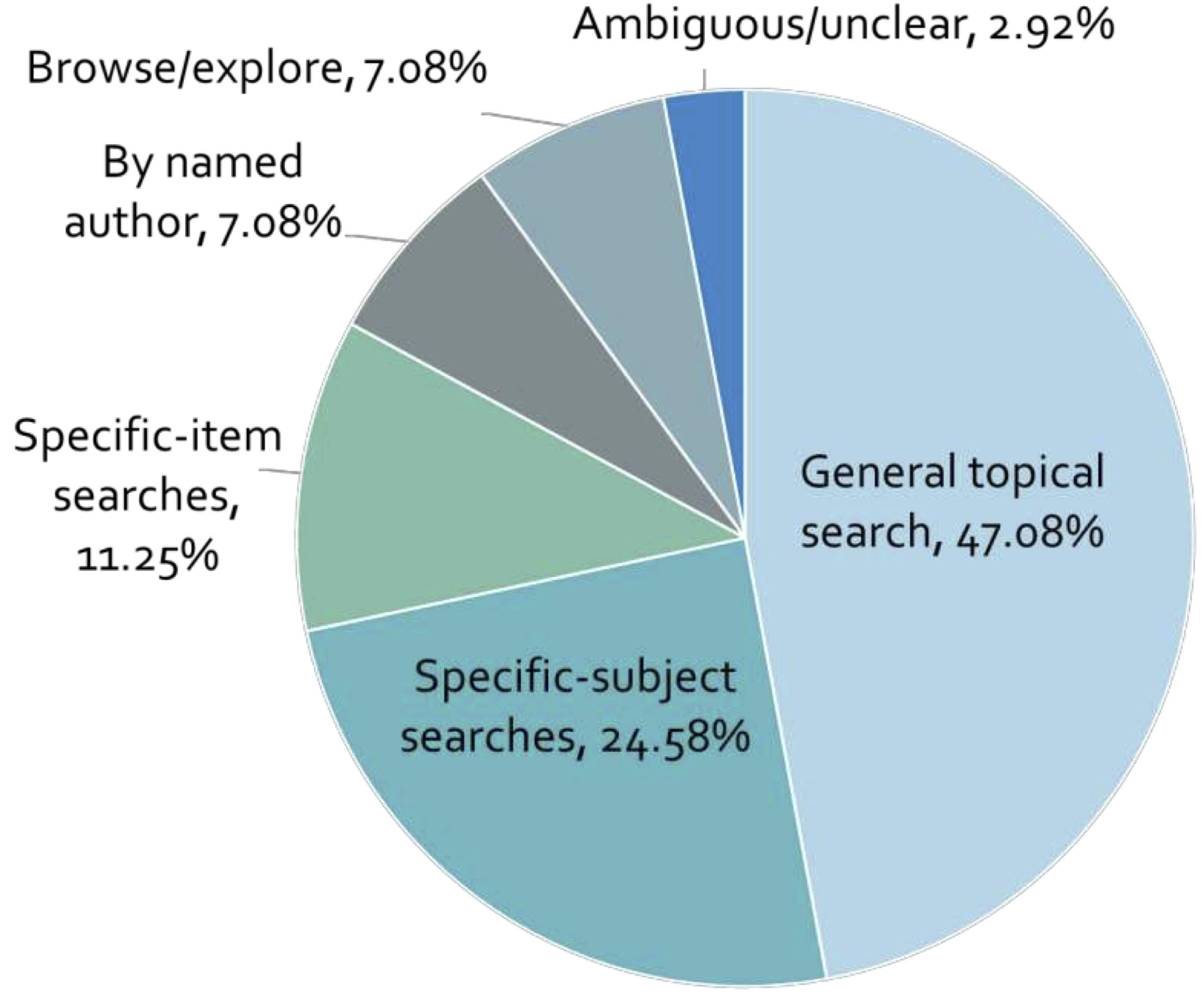

The searching behaviour of these users is categorised as: general topical (47.08%), subject-specific (24.58%), specific item (11.25%), by named author (7.08%) and browse/explore (7.08%.

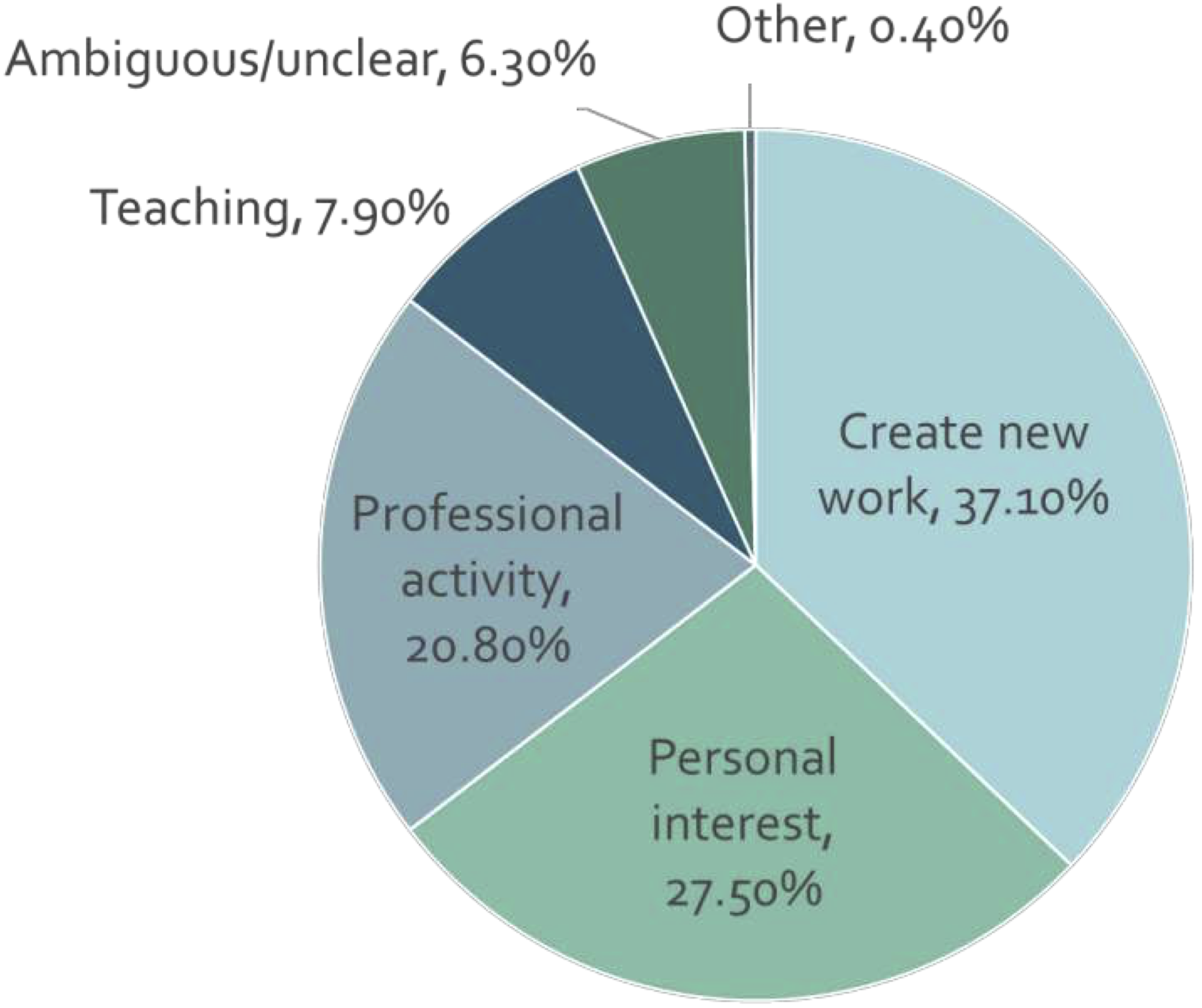

The motivations for searching include: create new work (37.1%), personal interest (27.5%), professional activity (20.8%) and teaching (7.9%).

(Note: Above pie charts from presentation by Monica Paramita.)

2019

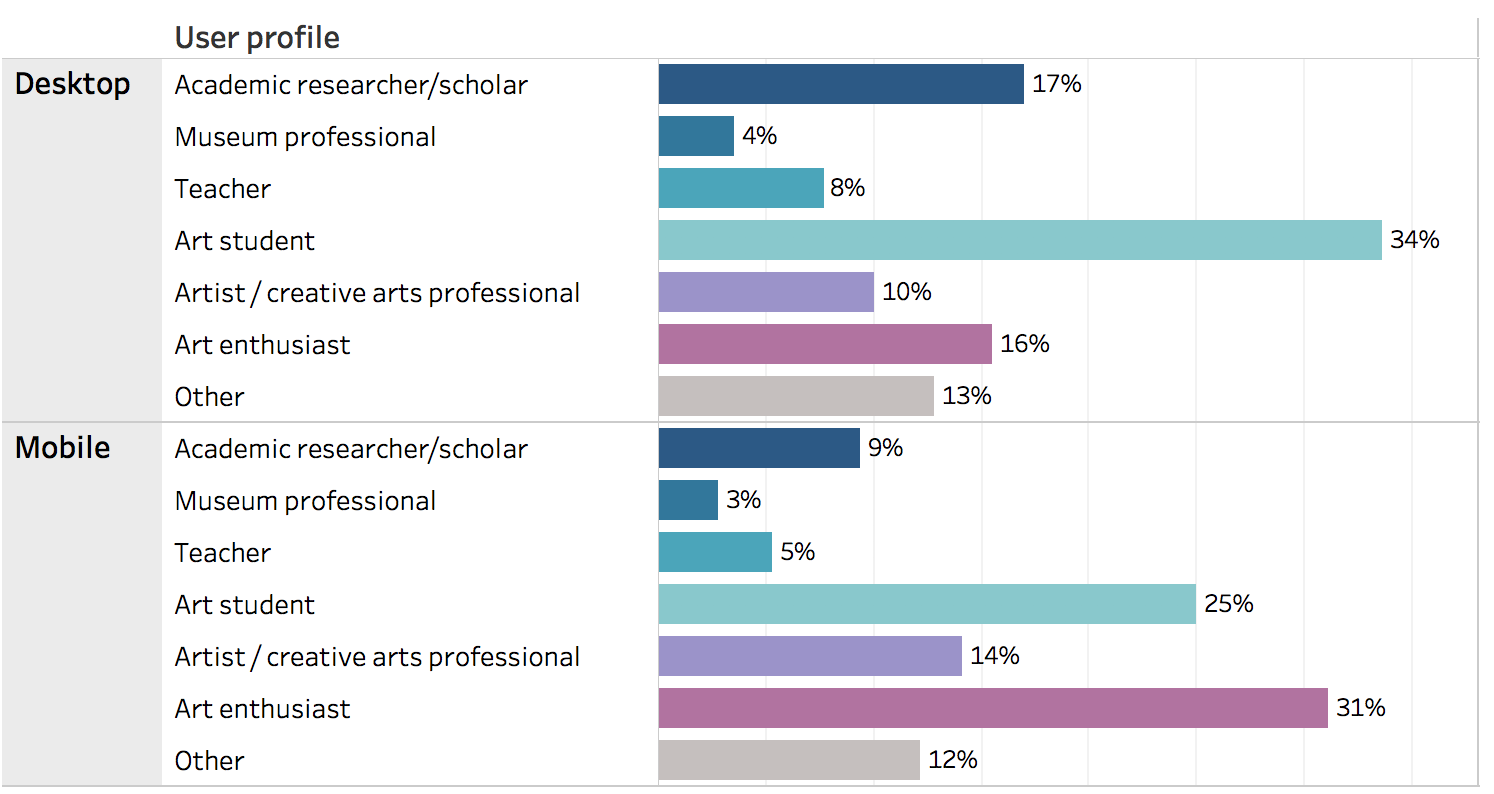

Follow-up research at the Met in 2019 by Elena Villaespesa, Bora Shehu and Tankha Madhav focused on the proportions of these audiences across desktop and mobile and web page features different audiences are looking for.

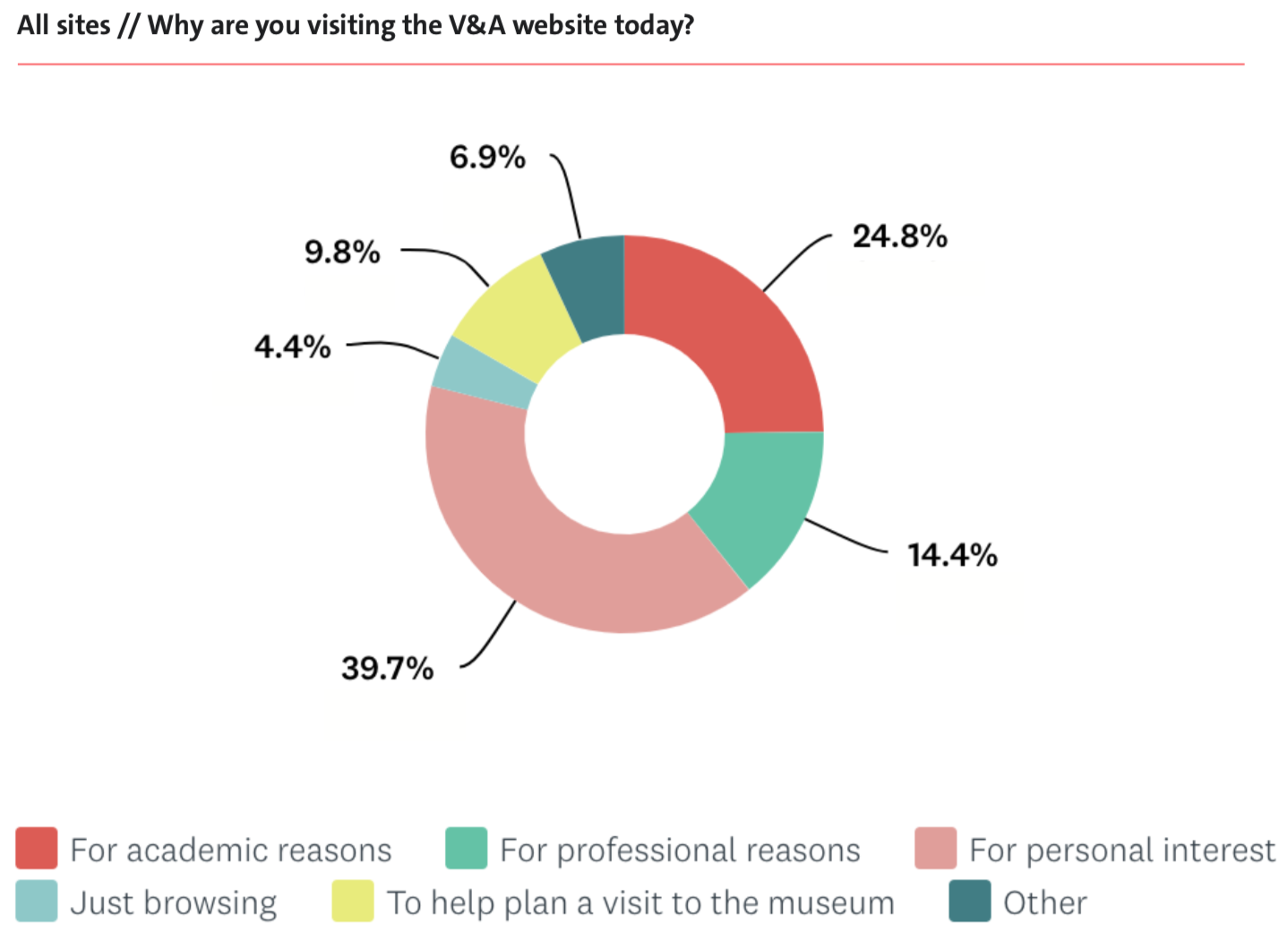

The V&A’s 2019 study of their online audiences highlighted personal interest as their largest audience motivation (39.7%), followed by academic (24.8%) and professional reasons (14.4%), with browsing being the smallest motivation (4.4%).

The blog post’s author, Jack Craig, summarises the further findings as follows:

- Most users visit for reasons of personal interest

- Most users don’t actually search Search the Collections

- Users want to tell us their stories

- Users can’t see how much information we have

- Imagery is key to many users experience

He goes on to identify a series of “modes modes of interaction”:

- Understand – people who are trying to get an overview of what’s in the collections or galleries with a view to digging deeper or visiting a museum.

- Explore – people who are looking to get inspired and want to be exposed to new ideas. They’re interested in a wide range of topics but they can feel overwhelmed by the choice so they tend to expect guidance and curation.

- Develop – people who are also looking for inspiration and knowledge but here it’s more directed to certain topics directly relevant to a particular project they’re working on. They rely on a combination of search and browse to make their results more specific and suitable to their needs.

- Research – people’s journeys in research mode might go through similar steps and behaviours as people in ‘develop’ but here they tend to be after deep information within a specific area rather than be open to moving sideways.

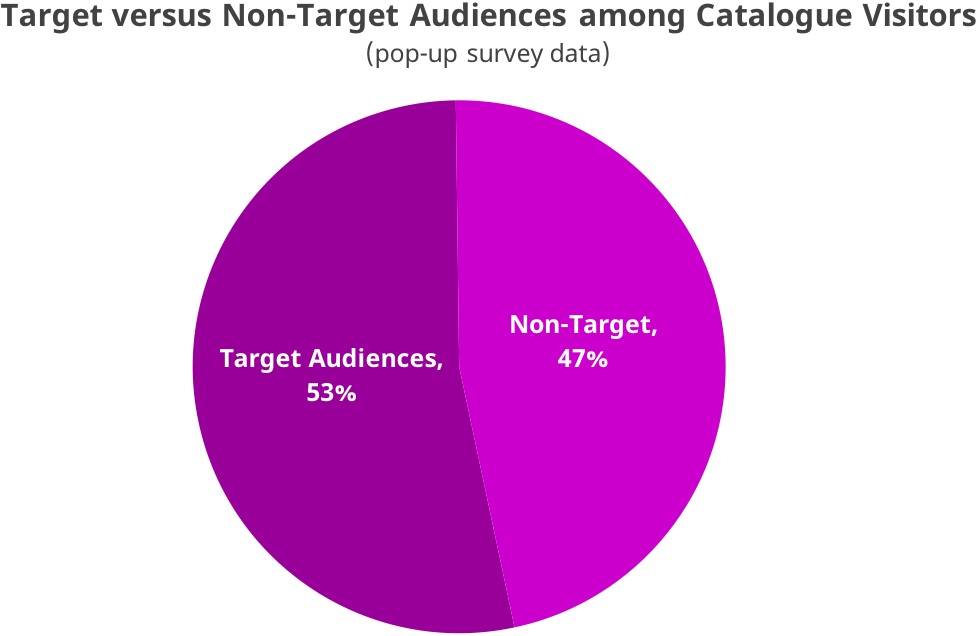

The 2019 Digital Catalogues Study: A cross-institutional user study of online museum collection catalogues reviewed scholarly online publications from four institutions: Art Institute of Chicago, the J. Paul Getty Museum, the National Gallery of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. These publications had their origins in print publications that were reimagined for online publication. Their target audiences are scholars/researchers; museum professionals and volunteers; professors; graduate and undergraduate students; librarians/archivists; and journal editors. Notably, almost half (47%) of the audiences were not within the target audiences.

Summary

- Audiences are diverse.

- Different websites have different proportions of these audiences.

- Different audiences have different needs and use the websites accordingly.

- Some audiences will have in-depth domain knowledge. Others will not.

- Some websites have behaviours not seen elsewhere (e.g. “inspiration” on art websites).

- Significant proportions of audiences have quite open-ended goals: browsing, inspiration, broad topic searches, etc.

- Search still dominates discovery.